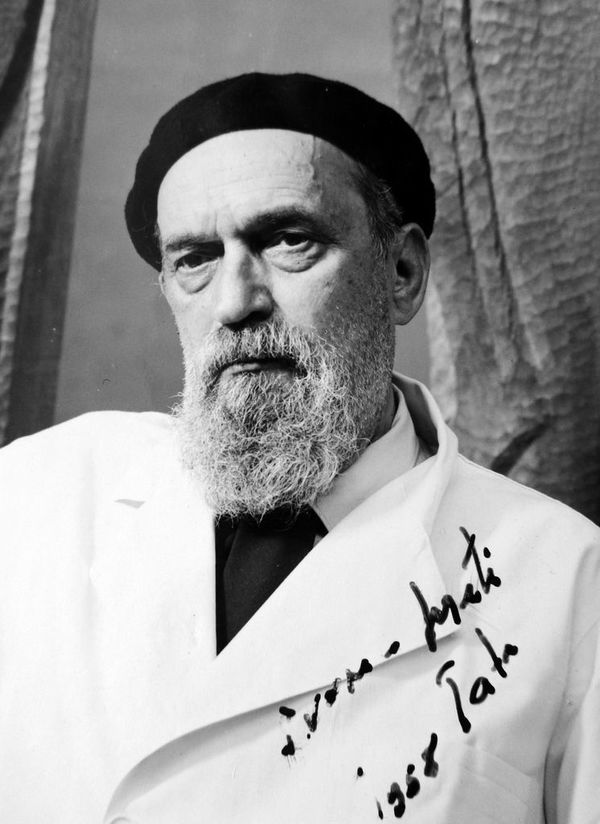

Ivan Mestrovic

Ivan Meštrović (1883–1962) was a Croatian sculptor and deeply devoted Catholic who expressed his insight into the beauty of the mysteries of Christianity through his art. Born in the village of Vrpolje, he was profoundly affected as a child by hearing the Croatian epics, songs, folktales, and parables from the Bible passed down through generations. Those nationalistic themes would heavily influence his later work as a sculptor, until a realization later in life that his love for the Croatian people must extend to all peoples, and thus to God.

Meštrović, the son of a stonemason, was apprenticed to a stonecutter at age 16. Through the generosity of local benefactors, he eventually attended the Vienna Art Academy, where he became good friends with Auguste Rodin, who later called Meštrović a greater artist than himself.

Meštrović’s greatest influences, however, were the Croatian culture and people. His love for his country and deep desire to see the Croats free and flourishing were not only expressed in his art but also through his political activism. At the beginning of World War I, he supported the Yugoslavian Committee of National Liberation, an organization formed to resist Italy’s attempt to seize parts of Dalmatia. As his popularity as an artist grew, his high profile as an accomplished artist made his political activism dangerous, and at the outbreak of World War I, Meštrović was forced to flee Croatia because of his vocal political convictions.

Meštrović spent the interim between World War I and World War II living in Yugoslavia. During this time he divorced his first wife, Ruza Klein, whom he had married in 1904, and later married Olga Kestercanek, with whom he had four children and would spend the rest of his life. He became a professor and spent 20 years as the director of the Art Institute of Zagreb, donating all his wages so that poor students could study art.

World War II plunged Meštrović’s life into tumult: After insulting Hitler by declining his invitation to exhibit in Berlin, Meštrović was arrested at the outbreak of the war and held in Savska Cesta prison for five months. He passed the time in his cell sketching plans for future religious sculptures, including his Pieta. After his release from prison (through a petition from the Vatican), Meštrović lived in Rome for a time before moving to Switzerland, where he suffered a severe, yearlong illness and worry over the fate of several family members: His daughter was gravely ill, his brother had been imprisoned, and his first wife died in the course of the war, along with thirty of her family members—who, owing to their Jewish descent, were murdered in the Holocaust.

After the war, Meštrović returned to Rome for a while, unable to bring himself to accept an invitation to return to Yugoslavia from Marshall Tito, whom he detested. Eventually he accepted a position as professor at Syracuse University in 1947, moving his wife and his youngest son to America. Later that year, he had his own show in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the first one-man show ever to take place there. Seven years later, President Eisenhower made him an American citizen.

In 1955, Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C., then-president of the University of Notre Dame, asked Meštrović to teach and work at Notre Dame. Meštrović accepted the invitation, considering Notre Dame to be the perfect environment to continue his religious sculpture. Sadly, the end of his life was clouded by the deaths of his daughter Marta and his son Tvrtko; four of his last works were a reflection of his grief those deaths. He visited Yugoslavia one last time before his own death, donating 59 of his works to churches, convents, and communities in his homeland at the request of his people. He taught at Notre Dame until his death in 1962, though his works still dot the campus to this day.

My later work grows naturally out of my earlier…. They attempted to be an expression of the history of the soul of our nation, the soul which in its essence is general and human…. Immediately after the Balkan War, and even more after the First World War I came to believe that the ideals of one nation are too small…. It was following the thread of these ideas and emotions that brought me to the Bible. A feeling of the general suffering of man then took a stronger place than for the suffering of a single nation. The need to overcome one particular evil, our evil, widened into need to overcome evil in general wherever it was and whosoever it was…. The best way to fight against evil is to pray to God; and to struggle for the beautiful means to sing his praises. (“About My Art”)

My art is expressed in hard wood and stone, but that which is in art is not in wood or stone, it is outside time and space. Art is a song and a prayer at the same time. (“About My Art”)

I believe that the sun will some out and warm the earth. I believe that women will bear children and the fields crops. I believe that love and blistered hands will always build and not destroy. It is only the mindless and the parasites that destroy. I believe that evil men will not prevent the good. I believe that chemistry will not destroy and neither will it lead to the salvation of mankind. I believe that prosperity is not the prime mover of the world and that stock exchanges, banks and customs barriers will not bring harmony, nor wealth nor justice.… (Preface to exhibition catalogue in Zagreb, 1932)

As in other things so too in art our century is not the worst, only it suffers more than other centuries from a longing for what it is not, and from imagining that it is what it is not. For example, in no previous century has so much been written about the individual and the original, and in almost no century has there been less that in fact is individual and original…. (Preface to the monograph, 1933)

Sources

Rev. Anthony J. Lauck, C.S.C., Dean A. Porter, Steven Alan Bennet, and Dan Vogl, Ivan Meštrović at Notre Dame. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame/Snite Museum of Art, 2003.

Duško Keckemet, Ivan Meštrović, tr. Sonia Wild Bicanic, ed. Dragutin Zdumic. Zagreb: Spektar, 1970.

Ivan Meštrović Papers, University of Notre Dame Archives.